-

Francia

France: Ambush marketing and the Paris 2024 Olympic Games

4 marzo 2024

- Contratos de distribución

- Patentes y Marcas

El agente comercial tiene derecho a obtener cierta información sobre las ventas del empresario. La Ley española del Contrato de Agencia prevé (15.2 LCA) que el agente tiene derecho a exigir la exhibición de la contabilidad del empresario para verificar todo lo relativo a las comisiones que le correspondan. Y también a que se le proporcionen las informaciones de que disponga el empresario y que sean necesarias para verificar la cuantía de dichas comisiones.

Este artículo está en consonancia con lo previsto en la Directiva sobre los agentes comerciales de 1986 según la cual (12.3) el agente tendrá derecho a exigir que se le proporcionen todas las informaciones que se hallen a disposición del empresario, en particular un extracto de los libros de contabilidad, que le sean necesarias para verificar el importe de las comisiones que le correspondan. Esto no podrá alterarse en detrimento del agente comercial mediante pacto.

La pregunta es ¿permanece este derecho incluso tras la terminación del contrato de agencia? En otras palabras: extinguido el contrato de agencia, ¿puede el agente solicitar la información y documentación mencionada en estos artículos y está el empresario obligado a proporcionársela?

En nuestra opinión, la norma no dice nada que limite este derecho, más bien cabe pensar lo contrario. Por lo que, en la medida en que persista alguna posible comisión que pueda nacer de dicha verificación, la respuesta ha de ser afirmativa. Veamos.

El derecho a exigir la exhibición de la contabilidad existe para que el agente pueda verificar la cuantía de las comisiones. Y el agente tiene derecho a comisiones por actos y operaciones concluidos durante la vigencia del contrato (art. 12 LCA), pero también por actos u operaciones concluidos con posterioridad a la extinción del contrato (art. 13 LCA), y por operaciones no ejecutadas por circunstancias imputables al empresario (art. 17 LCA). Además, el agente tiene derecho a que la comisión se devengue en el momento en que hubiera debido ejecutarse el acto u operación (art. 14 LCA).

Todas estas operaciones pueden tener lugar una vez concluido el contrato. Piénsese en la situación habitual en la que los pedidos se cursan durante el contrato, pero son aceptados o ejecutados con posterioridad. Reducir el derecho del agente a informarse solo durante la vigencia del contrato sería limitar indebidamente su derecho a la comisión correspondiente. Y téngase en cuenta que el importe de las comisiones durante los últimos cinco años puede, además, influir en el cálculo de la indemnización por clientela (art. 28 LCA), por lo que el interés del agente para conocerlas es doble: lo que percibiría como comisión, y lo que podría aumentar la base para una futura indemnización.

Esto ha sido confirmado, por ejemplo, por la Audiencia de Madrid (AAP 227/2017, de 29 de junio [ECLI:ES:APM:2017:2873A]) que textualmente dice:

[…] el art. 15.2 de la ley de Contrato de Agencia dispone el derecho del agente a exigir la exhibición de la contabilidad del empresario en los particulares necesarios para verificar todo lo relativo a las comisiones que le corresponden, como a serle proporcionadas las informaciones de que disponga el empresario y sean necesarias para verificar su cuantía. A ello no es óbice, […], que el contrato de agencia ya hubiese sido resuelto pues ello no implica que dejasen de devengarse comisiones por pólizas, contratadas con la mediación del agente, que mantengan su vigencia.

Cabe preguntarse entonces si este derecho de información es ilimitado en el tiempo. Y aquí la respuesta sería negativa. La limitación del derecho a recibir información estaría vinculada a la prescripción del derecho a reclamar la correspondiente comisión. Si el derecho a percibir la comisión estuviera indudablemente prescrito, podría defenderse que no cabría recibir información sobre ella. Pero para tal excepción, la prescripción debe ser clara, por lo tanto, considerando las posibles interrupciones habidas por reclamaciones incluso extrajudiciales. En caso de duda, será necesario reconocer el derecho a exigir la información, sin perjuicio de que luego se invoque y reconozca la imposibilidad de reclamar la comisión si estuviera prescrito el derecho. Y para ello debemos considerar el plazo de prescripción para exigir las comisiones (en general, tres años) y la del derecho para reclamar la indemnización por clientela (un año).

En resumen: no parece que el derecho a recibir información y al examen de la documentación del empresario quede limitado por la vigencia del contrato de agencia; aunque, por otra parte, convenga analizar la posible prescripción para exigir las comisiones. En caso de no tener una respuesta clara sobre ésta, el derecho de información debería, en nuestra opinión, prevalecer, sin perjuicio de que el resultado pueda luego no dar derecho a la reclamación por haber prescrito.

SUMMARY: In large-scale events such as the Paris Olympics certain companies will attempt to «wildly» associate their brand with the event through a practice called «ambush marketing», defined by caselaw as «an advertising strategy implemented by a company in order to associate its commercial image with that of an event, and thus to benefit from the media impact of said event, without paying the related rights and without first obtaining the event organizer’s authorization» (Paris Court of Appeal, June 8, 2018, Case No 17/12912). A risky and punishable practice, that might sometimes yet be an option yet.

Key takeaways

- Ambush marketing might be a punished practice but is not prohibited as such;

- As a counterpart of their investment, sponsors and official partners benefit from an extensive legal protection against all forms of ambush marketing in the event concerned, through various general texts (counterfeiting, parasitism, intellectual property) or more specific ones (e.g. sport law);

- The Olympics Games are subject to specific regulations that further strengthen this protection, particularly in terms of intellectual property.

- But these rights are not absolute, and they are still thin opportunities for astute ambush marketing.

The protection offered to sponsors and official partners of sporting and cultural events from ambush marketing

With a budget of over 4 billion euros, the 2024 Olympic and Paralympic Games are financed mostly by various official partners and sponsors, who in return benefit from a right to use Olympic and Paralympic properties to be able to associate their own brand image and distinctive signs with these events.

Ambush marketing is not punishable as such under French law, but several scattered texts provide extensive protection against ambush marketing for sponsors and partners of sporting or cultural continental-wide or world-wide events. Indeed, sponsors are legitimately entitled to peacefully enjoy the rights offered to them in return for large-scale investments in events such as the FIFA or rugby World Cups, or the Olympic Games.

In particular, official sponsors and organizers of such events may invoke:

- the «classic» protections offered by intellectual property law (trademark law and copyright) in the context of infringement actions based on the French Intellectual Property Code,

- tort law (parasitism and unfair competition based on article 1240 of the French Civil Code);

- consumer law (misleading commercial practices) based on the French Consumer Code,

- but also more specific texts such as the protection of the exploitation rights of sports federations and sports event organizers derived from the events or competitions they organize, as set out in article L.333-1 of the French Sports Code, which gives sports event organizers an exploitation monopoly.

The following ambush marketing practices were sanctioned on the abovementioned grounds:

- The use of a tennis competition name and of the trademark associated with it during the sporting event: The organization of online bets, by an online betting operator, on the Roland Garros tournament, using the protected sign and trademark Roland Garros to target the matches on which the bets were organized. The unlawful exploitation of the sporting event, was punished and 400 K€ were allowed as damages, based on article L. 333-1 of the French Sports Code, since only the French Tennis Federation (F.F.T.) owns the right to exploit Roland Garros. The use of the trademark was also punished as counterfeiting (with 300 K€ damages) and parasitism (with 500 K€ damages) (Paris Court of Appeal, Oct. 14, 2009, Case No 08/19179);

- An advertising campaign taking place during a film festival and reproducing the event’s trademark: The organization, during the Cannes Film Festival, of a digital advertising campaign by a cosmetics brand through the publication on its social networks of videos showing the beauty makeovers of the brand’s muses, in some of which the official poster of the Cannes Film Festival was visible, one of which reproduced the registered trademark of the “Palme d’Or”, was punished on the grounds of copyright infringement and parasitism with a 50 K€ indemnity (Paris Judicial Court, Dec. 11, 2020, Case No19/08543);

- An advertising campaign aimed at falsely claiming to be an official partner of an event: The use, during the Cannes Film Festival, of the slogan «official hairdresser for women» together with the expressions «Cannes» and «Cannes Festival», and other publications falsely leading the public to believe that the hairdresser was an official partner, to the detriment of the only official hairdresser of the Cannes festival, was punished on the grounds of unfair competition and parasitism with a 50 K€ indemnity (Paris Court of Appeal, June 8, 2018, Case No 17/12912).

These financial penalties may be combined with injunctions to cease these behaviors, and/or publication in the press under penalty.

An even greater protection for the Paris 2024 Olympic Games

The Paris 2024 Olympic Games are also subject to specific regulations.

Firstly, Article L.141-5 of the French Sports Code, enacted for the benefit of the «Comité national olympique et sportif français” (CNOSF) and the “Comité de l’organisation des Jeux Olympiques et Paralympiques de Paris 2024” (COJOP), protects Olympic signs such as the national Olympic emblems, but also the emblems, the flag, motto and Olympic symbol, Olympic anthem, logo, mascot, slogan and posters of the Olympic Games, the year of the Olympic Games «city + year», the terms «Jeux Olympiques», «Olympisme», «Olympiade», «JO», «olympique», «olympien» and «olympienne». Under no circumstances may these signs be reproduced or even imitated by third-party companies. The COJOP has also published a guide to the protection of the Olympic trademark, outlining the protected symbols, trademarks and signs, as well as the protection of the official partners of the Olympic Games.

Secondly, Law no. 2018-202 of March 26, 2018 on the organization of the 2024 Olympic and Paralympic Games adds even more specific prohibitions, such as the reservation for official sponsors of advertising space located near Olympic venues, or located on the Olympic and Paralympic torch route. This protection is unique in the context of the Olympic Games, but usually unregulated in the context of simple sporting events.

The following practices, for example, have already been sanctioned on the above-mentioned grounds:

- Reproduction of a logo imitating the well-known «Olympic» trademark on a clothing collection: The marketing of a collection of clothing, during the 2016 Olympic Games, bearing a logo (five hearts in the colors of the 5 Olympic colors intersecting in the image of the Olympic logo) imitating the Olympic symbol in association with the words «RIO» and «RIO 2016», was punished on the grounds of parasitism (10 K€ damages) and articles L. 141-5 of the French Sports Code (35 K€) and L. 713-1 of the French Intellectual Property Code (10 K€ damages) (Paris Judicial Court, June 7, 2018, Case No16/10605);

- The organization of a contest on social networks using protected symbols: During the 2018 Olympic Games in PyeongChang, a car rental company organized an online game inviting Internet users to nominate the athletes they wanted to win a clock radio, associated with the hashtags «#JO2018» («#OJ2018”), «#Jeuxolympiques» (“#Olympicsgame”) or «C’est parti pour les jeux Olympiques» (“let’s go for the Olympic Games”) without authorization from the CNOSF, owner of these distinctive signs under the 2018 law and article L.141-5 of the French Sport Code and punished on these grounds with 20 K€ damages and of 10 K€ damages for parasitism (Paris Judicial Court, May 29, 2020, n°18/14115).

These regulations offer official partners greater protection for their investments against ambush marketing practices from non-official sponsors.

Some marketing operations might be exempted

An analysis of case law and promotional practices nonetheless reveals the contours of certain advertising practices that could be authorized (i.e. not sanctioned by the above-mentioned texts), provided they are skillfully prepared and presented. Here are a few exemples :

- Communication in an offbeat or humorous tone: An offbeat or even humorous approach can help to avoid the above-mentioned sanctions:

In 2016, for example, the Intersnack group’s Vico potato chips brand launched a promotional campaign around the slogan «Vico, partner of home fans» in the run-up to the Euro and Olympic Games.

Irish online betting company Paddy Power had sponsored a simple egg-in-the-spoon race in «London» (… a village in Burgundy, France), to display in London during the 2012 Olympics the slogan «Official Sponsor of the largest athletics event in London this year! There you go, we said it. (Ahem, London France that is)«. At the time, the Olympic Games organizing committee failed to stop the promotional poster campaign.

During Euro 2016, for which Carlsberg was the official sponsor, the Dutch group Heineken marketed a range of beer bottles in the colors of the flags of 21 countries that had «marked its history», the majority of which were however participating in the competition.

- Communication of information for advertising purposes: The use of the results of a rugby match and the announcement of a forthcoming match in a newspaper to promote a motor vehicle and its distinctive features was deemed lawful: «France 13 Angleterre 24 – the Fiat 500 congratulates England on its victory and looks forward to seeing the French team on March 9 for France-Italy» (France 13 Angleterre 24 – la Fiat 500 félicite l’Angleterre pour sa victoire et donne rendez-vous à l’équipe de France le 9 mars pour France-Italie) the judges having considered that this publication «merely reproduces a current sporting result, acquired and made public on the front page of the sports newspaper, and refers to a future match also known as already announced by the newspaper in a news article» (Court of cassation, May 20, 2014, Case No 13-12.102).

- Sponsorship of athletes, including those taking part in Olympic competitions: Subject to compliance with the applicable regulatory framework, particularly as regards models, any company may enter into partnerships with athletes taking part in the Olympic Games, for example by donating clothing bearing the desired logo or brand, which they could wear during their participation in the various events. Athletes may also, under certain conditions, broadcast acknowledgements from their partner (even if unofficial). Rule 40 of the Olympic Charter governs the use of athletes’, coaches’ and officials’ images for advertising purposes during the Olympic Games.

The combined legal and marketing approach to the conception and preparation of the message of such a communication operation is essential to avoid legal proceedings, particularly on the grounds of parasitism; one might therefore legitimately contemplate advertising campaigns, particularly clever, or even malicious ones.

In this first episode of Legalmondo’s Distribution Talks series, I spoke with Ignacio Alonso, a Madrid-based lawyer with extensive experience in international commercial distribution.

Main discussion points:

- in Spain, there is no specific law for distribution agreements, which are governed by the general rules of the Commercial Code;

- therefore, it is essential to draft a clear and comprehensive contract, which will be the primary source of the parties’ rights and obligations;

- it is also good to be aware of Spanish case law on commercial distribution, which in some cases applies the law on commercial agency by analogy.

- the most common issues involving foreign producers distributing in Spain arise at the time of termination of the relationship, mainly because case law grants the terminated distributor an indemnity of clientele or goodwill if similar prerequisites to those in the agency regulations apply.

- another frequent dispute concerns the adequacy of the notice period for terminating the contract, especially if there is no agreement between the parties: the advice is to follow what the agency regulations stipulate and thus establish a minimum notice period of one month for each year of the contract’s duration, up to 6 months for agreements lasting more than five years;

- regarding dispute resolution tools, mediation is an option that should be carefully considered because it is quick, inexpensive, and allows a shared solution to be sought flexibly without disrupting the business relationship.

- if mediation fails, the parties can provide for recourse to arbitration or state court. The choice depends on the case’s specific circumstances, and one factor in favor of jurisdiction is the possibility of appeal, which is excluded in the case of arbitration.

Go deeper

- Goodwill or clientele indemnity, when it is due and how to calculate it: see this article and on our blog;

- Practical Guide on International Distribution Contract: Spain report

- Practical Guide on International Agency Contract: Spain report

- Mediation: The importance of mediation in distribution contracts

- How to negotiate and draft an international distribution agreement: 7 lessons from the history of Nike

Summary

On 1 June 2022, Regulation EU n. 720/2022, i.e.: the new Vertical Block Exemption Regulation (hereinafter: «VBER»), replaced the previous version (Regulation EU n. 330/2010), expired on 31 May 2022.

The new VBER and the new vertical guidelines (hereinafter: “Guidelines”) have received the main evidence gathered during the lifetime of the previous VBER and contain some relevant provisions affecting the discipline of all B2B agreements among businesses operating at different levels of the supply chain.

In this article, we will focus on the impact of the new VBER on sales through digital platforms, listing the main novelties impacting distribution chains, including a platform for marketing products/services.

The general discipline of vertical agreements

Article 101(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (“TFEU”) prohibits all agreements that prevent, restrict, or distort competition within the EU market, listing the main types, e.g.: price fixing; market partitioning; limitations on production/development/investment; unfair terms, etc.

However, Article 101(3) TFEU exempts from such restrictions the agreements that contribute to improving the EU market, to be identified in a special category Regulation.

The VBER establishes the category of vertical agreements (i.e., agreements between businesses operating at different levels of the supply chain), determining which of these agreements are exempted from Article 101(1) TFEU prohibition.

In short, vertical agreements are presumed to be exempted (and therefore valid) if they do not contain so-called «hardcore restrictions» (i.e., severe restrictions of competition, such as an absolute ban on sales in a territory or the manufacturer’s determination of the distributor’s resale price) and if neither party’s market share exceeds 30%.

The exempted agreements benefit from what has been termed the “safe harbour” of the VBER. In contrast, the others will be subject to the general prohibition of Article 101(1) TFEU unless they can benefit from an individual exemption under Article 101(3) TFUE.

The innovations introduced by the new VBER to online platforms

The first relevant aspect concerns the classification of the platforms, as the European Commission excluded that the online platform generally meets the conditions to be categorized as agency agreements.

While there have never been doubts concerning platforms that operate by purchasing and reselling products (classic example: Amazon Retail), some have arisen concerning those platforms that merely promote the products of third parties without carrying out the activity of resale (classic example: Amazon Marketplace).

With this statement, the European Commission wanted to clear the field of doubt, making explicit that intermediation service providers (such as online platforms) qualify as suppliers (as opposed to commercial agents) under the VBER. This reflects the approach of Regulation (EU) 2019/1150 («P2B Regulation»), which has, for the first time, dictated a specific discipline for digital platforms. It provided for a set of rules to create a “fair, transparent, and predictable environment” for smaller businesses and customers” and for the rationale of the Digital Markets Act, banning certain practices used by large platforms acting as “gatekeepers”.

Therefore, all contracts concluded between manufacturers and platforms (defined as ‘providers of online intermediation services’) are subject to all the restrictions imposed by the VBER. These include the price, the territories to which or the customers to whom the intermediated goods or services may be sold, or the restrictions relating to online advertising and selling.

Thus, to give an example, the operator of a platform may not impose a fixed or minimum sale price for a transaction promoted through the platform.

The second most impactful aspect concerns hybrid platforms, i.e., competing in the relevant market to sell intermediated goods or services. Amazon is the most well-known example, as it is a provider of intermediation services (“Amazon Marketplace”), and – at the same time – it distributes the products of those parties (“Amazon Retail”). We have previously explored the distinction between those 2 business models (and the consequences in terms of intellectual property infringement) here.

The new VBER explicitly does not apply to hybrid platforms. Therefore, the agreements concluded among such platforms and manufacturers are subject to the limitations of the TFEU, as such providers may have the incentive to favour their sales and the ability to influence the outcome of competition between undertakings that use their online intermediation services.

Those agreements must be assessed individually under Article 101 of the TFEU, as they do not necessarily restrict competition within the meaning of TFEU, or they may fulfil the conditions of an individual exemption under Article 101(3) TFUE.

The third very relevant aspect concerns the parity obligations (also referred to as Most Favoured Nation Clauses, or MFNs), i.e., the contract provisions in which a seller (directly or indirectly) agrees to give the buyer the best terms it makes available to any other buyer.

Indeed, platforms’ contractual terms often contain parity obligation clauses to prevent users from offering their products/services at lower prices or on better conditions on their websites or other platforms.

The new VBER deals explicitly with parity clauses, making a distinction between clauses whose purpose is to prohibit users of a platform from selling goods or services on more favourable terms through competing platforms (so-called “wide parity clauses”), and clauses that prohibit sales on more favourable terms only in respect of channels operated directly by the users (so-called “narrow parity clauses”).

Wide parity clauses do not benefit from the VBER exemption; therefore, such obligations must be assessed individually under Article 101(3) TFEU.

On the other hand, narrow parity clauses continue to benefit from the exemption already granted by the old VBER if they do not exceed the threshold of 30% of the relevant market share set out in Article 3 of the new VBER. However, the new Guidelines warn against using overly narrow parity obligations by online platforms covering a significant share of users, stating that if there is no evidence of pro-competitive effects, the benefit of the block exemption is likely to be withdrawn.

Impact and takeaways

The new VBER entered into force on 1 June 2022 and is already applicable to agreements signed after that date. Agreements already in force on 31 May 2022 that satisfy the conditions for exemption under the current VBER but do not satisfy the requirements under the new VBER shall benefit from a one-year transitional period.

The new regime will be the playing field for all platform-driven sales over the next 12 years (the regulation expires on 31 May 2034). Currently, the rather restrictive novelties on hybrid platforms and parity obligations will likely necessitate substantial revisions to existing trade agreements.

Here, then, are some tips for managing contracts and relationships with online platforms:

- the new VBER is the right opportunity to review the existing distribution networks. The revision will have to consider not only the new regulatory limits (e.g., the ban on wide parity clauses) but also the new discipline reserved for hybrid platforms and dual distribution to coordinate the different distribution channels as efficiently as possible, by the stakes set by the new VBER and the Guidelines;

- platforms are likely to play an even greater role during the next decade; it is, therefore, essential to consider these sales channels from the outset, coordinating them with the other existing ones (retail, direct sales, distributors, etc.) to avoid jeopardizing the marketing of products or services;

- the European legislator’s attention toward platforms is growing. Looking up from the VBER, one should not forget that they are subject to a multitude of other European regulations, which are gradually regulating the sector and which must be considered when concluding contracts with platforms. The reference is not only to the recent Digital Market Act and P2B Regulation but also to the protection of IP rights on platforms, which – as we have already seen – is still an open issue.

Summary

To avoid disputes with important suppliers, it is advisable to plan purchases over the medium and long term and not operate solely on the basis of orders and order confirmations. Planning makes it possible to agree on the duration of the ‘supply agreement, minimum volumes of products to be delivered and delivery schedules, prices, and the conditions under which prices can be varied over time.

The use of a framework purchase agreement can help avoid future uncertainties and allows various options to be used to manage commodity price fluctuations depending on the type of products , such as automatic price indexing or agreement to renegotiate in the event of commodity fluctuations beyond a certain set tolerance period.

I read in a press release: “These days, the glass industry is sending wine companies new unilateral contract amendments with price changes of 20%…”

What can one do to avoid the imposition of price increases by suppliers?

- Know your rights and act in an informed manner

- Plan and organise your supply chain

Does my supplier have the right to increase prices?

If contracts have already been concluded, e.g., orders have already been confirmed by the supplier, the answer is often no.

It is not legitimate to request a price change. It is much less legitimate to communicate it unilaterally, with the threat of cancelling the order or not delivering the goods if the request is not granted.

What if he tells me it is force majeure?

That’s wrong: increased costs are not a force majeure but rather an unforeseen excessive onerousness, which hardly happens.

What if the supplier canceled the order, unilaterally increased the price, or did not deliver the goods?

He would be in breach of contract and liable to pay damages for violating his contractual obligations.

How can one avoid a tug-of-war with suppliers?

The tools are there. You have to know them and use them.

It is necessary to plan purchases in the medium term, agreeing with suppliers on a schedule in which are set out:

- the quantities of products to be ordered

- the delivery terms

- the durationof the agreement

- the pricesof the products or raw materials

- the conditions under which prices can be varied

There is a very effective instrument to do so: a framework purchase agreement.

Using a framework purchase agreement, the parties negotiate the above elements, which will be valid for the agreed period.

Once the agreement is concluded, product orders will follow, governed by the framework agreement, without the need to renegotiate the content of individual deliveries each time.

For an in-depth discussion of this contract, see this article.

- “Yes, but my suppliers will never sign it!”

Why not? Ask them to explain the reason.

This type of agreement is in the interest of both parties. It allows planning future orders and grants certainty as to whether, when, and how much the parties can change the price.

In contrast, acting without written agreements forces the parties to operate in an environment of uncertainty. Suppliers can request price increases from one day to the next and refuse supply if the changes are not accepted.

How are price changes for future supplies regulated?

Depending on the type of products or services and the raw materials or energy relevant in determining the final price, there are several possibilities.

- The first option is to index the price automatically. E.g., if the cost of a barrel of Brent oil increases/decreases by 10%, the party concerned is entitled to request a corresponding adjustment of the product’s price in all orders placed as of the following week.

- An alternative is to provide for a price renegotiation in the event of a fluctuation of the reference commodity. E.g., suppose the LME Aluminium index of the London Stock Exchange increases above a certain threshold. In that case, the interested party may request a price renegotiationfor orders in the period following the increase.

What if the parties do not agree on new prices?

It is possible to terminate the contract or refer the price determination to a third party, who would act as arbitrator and set the new prices for future orders.

Summary

The framework supply contract is an agreement that regulates a series of future sales and purchases between two parties (customer and supplier) that take place over a certain period of time. This agreement determines the main elements of future contracts such as price, product volumes, delivery terms, technical or quality specifications, and the duration of the agreement.

The framework contract is useful for ensuring continuity of supply from one or more suppliers of a certain product that is essential for planning industrial or commercial activity. While the general terms and conditions of purchase or sale are the rules that apply to all suppliers or customers of the company. The framework contract is advisable to be concluded with essential suppliers for the continuity of business activity, in general or in relation to a particular project.

What I am talking about in this article:

- What is the supply framework agreement?

- What is the function of the supply framework agreement?

- The difference with the general conditions of sale or purchase

- When to enter a purchase framework agreement?

- When is it beneficial to conclude a sales framework agreement?

- The content of the supply framework agreement

- Price revision clause and hardship

- Delivery terms in the supply framework agreement

- The Force Majeure clause in international sales contracts

- International sales: applicable law and dispute resolution arrangements

What is a framework supply agreement?

It is an agreement that regulates a series of future sales and purchases between two parties (customer and supplier), which will take place over a certain period.

It is therefore referred to as a «framework agreement» because it is an agreement that establishes the rules of a future series of sales and purchase contracts, determining their primary elements (such as the price, the volumes of products to be sold and purchased, the delivery terms of the products, and the duration of the contract).

After concluding the framework agreement, the parties will exchange orders and order confirmations, entering a series of autonomous sales contracts without re-discussing the covenants already defined in the framework agreement.

Depending on one’s point of view, this agreement is also called a sales framework agreement (if the seller/supplier uses it) or a purchasing framework agreement (if the customer proposes it).

What is the function of the framework supply agreement?

It is helpful to arrange a framework agreement in all cases where the parties intend to proceed with a series of purchases/sales of products over time and are interested in giving stability to the commercial agreement by determining its main elements.

In particular, the purchase framework agreement may be helpful to a company that wishes to ensure continuity of supply from one or more suppliers of a specific product that is essential for planning its industrial or commercial activity (raw material, semi-finished product, component).

By concluding the framework agreement, the company can obtain, for example, a commitment from the supplier to supply a particular minimum volume of products, at a specific price, with agreed terms and technical specifications, for a certain period.

This agreement is also beneficial, at the same time, to the seller/supplier, which can plan sales for that period and organize, in turn, the supply chain that enables it to procure the raw materials and components necessary to produce the products.

What is the difference between a purchase or sales framework agreement and the general terms and conditions?

Whereas the framework agreement is an agreement that is used with one or more suppliers for a specific product and a certain time frame, determining the essential elements of future contracts, the general purchase (or sales) conditions are the rules that apply to all the company’s suppliers (or customers).

The first agreement, therefore, is negotiated and defined on a case-by-case basis. At the same time, the general conditions are prepared unilaterally by the company, and the customers or suppliers (depending on whether they are sales or purchase conditions) adhere to and accept that the general conditions apply to the individual order and/or future contracts.

The two agreements might also co-exist: in that case; it is a good idea to specify which contract should prevail in the event of a discrepancy between the different provisions (usually, this hierarchy is envisaged, ranging from the special to the general: order – order confirmation; framework agreement; general terms and conditions of purchase).

When is it important to conclude a purchase framework agreement?

It is beneficial to conclude this agreement when dealing with a mono-supplier or a supplier that would be very difficult to replace if it stopped selling products to the purchasing company.

The risks one aims to avoid or diminish are so-called stock-outs, i.e., supply interruptions due to the supplier’s lack of availability of products or because the products are available, but the parties cannot agree on the delivery time or sales price.

Another result that can be achieved is to bind a strategic supplier for a certain period by agreeing that it will reserve an agreed share of production for the buyer on predetermined terms and conditions and avoid competition with offers from third parties interested in the products for the duration of the agreement.

When is it helpful to conclude a sales framework agreement?

This agreement allows the seller/supplier to plan sales to a particular customer and thus to plan and organize its production and logistical capacity for the agreed period, avoiding extra costs or delays.

Planning sales also makes it possible to correctly manage financial obligations and cash flows with a medium-term vision, harmonizing commitments and investments with the sales to one’s customers.

What is the content of the supply framework agreement?

There is no standard model of this agreement, which originated from business practice to meet the requirements indicated above.

Generally, the agreement provides for a fixed period (e.g., 12 months) in which the parties undertake to conclude a series of purchases and sales of products, determining the price and terms of supply and the main covenants of future sales contracts.

The most important clauses are:

- the identification of products and technical specifications (often identified in an annex)

- the minimum/maximum volume of supplies

- the possible obligation to purchase/sell a minimum/maximum volume of products

- the schedule of supplies

- the delivery times

- the determination of the price and the conditions for its possible modification (see also the next paragraph)

- impediments to performance (Force Majeure)

- cases of Hardship

- penalties for delay or non-performance or for failure to achieve the agreed volumes

- the hierarchy between the framework agreement and the orders and any other contracts between the parties

- applicable law and dispute resolution (especially in international agreements)

How to handle price revision in a supply contract?

A crucial clause, especially in times of strong fluctuations in the prices of raw materials, transport, and energy, is the price revision clause.

In the absence of an agreement on this issue, the parties bear the risk of a price increase by undertaking to respect the conditions initially agreed upon; except in exceptional cases (where the fluctuation is strong, affects a short period, and is caused by unforeseeable events), it isn’t straightforward to invoke the supervening excessive onerousness, which allows renegotiating the price, or the contract to be terminated.

To avoid the uncertainty generated by price fluctuations, it is advisable to agree in the contract on the mechanisms for revising the price (e.g., automatic indexing following the quotation of raw materials). The so-called Hardship or Excessive Onerousness clause establishes what price fluctuation limits are accepted by the parties and what happens if the variations go beyond these limits, providing for the obligation to renegotiate the price or the termination of the contract if no agreement is reached within a certain period.

How to manage delivery terms in a supply agreement?

Another fundamental pact in a medium to long-term supply relationship concerns delivery terms. In this case, it is necessary to reconcile the purchaser’s interest in respecting the agreed dates with the supplier’s interest in avoiding claims for damages in the event of a delay, especially in the case of sales requiring intercontinental transport.

The first thing to be clarified in this regard concerns the nature of delivery deadlines: are they essential or indicative? In the first case, the party affected has the right to terminate (i.e., wind up) the agreement in the event of non-compliance with the term; in the second case, due diligence, information, and timely notification of delays may be required, whereas termination is not a remedy that may be automatically invoked in the event of a delay.

A useful instrument in this regard is the penalty clause: with this covenant, it is established that for each day/week/month of delay, a sum of money is due by way of damages in favor of the party harmed by the delay.

If quantified correctly and not excessively, the penalty is helpful for both parties because it makes it possible to predict the damages that may be claimed for the delay, quantifying them in a fair and determined sum. Consequently, the seller is not exposed to claims for damages related to factors beyond his control. At the same time, the buyer can easily calculate the compensation for the delay without the need for further proof.

The same mechanism, among other things, may be adopted to govern the buyer’s delay in accepting delivery of the goods.

Finally, it is a good idea to specify the limit of the penalty (e.g.,10 percent of the price of the goods) and a maximum period of grace for the delay, beyond which the party concerned is entitled to terminate the contract by retaining the penalty.

The Force Majeure clause in international sales contracts

A situation that is often confused with excessive onerousness, but is, in fact, quite different, is that of Force Majeure, i.e., the supervening impossibility of performance of the contractual obligation due to any event beyond the reasonable control of the party affected, which could not have been reasonably foreseen and the effects of which cannot be overcome by reasonable efforts.

The function of this clause is to set forth clearly when the parties consider that Force Majeure may be invoked, what specific events are included (e.g., a lock-down of the production plant by order of the authority), and what are the consequences for the parties’ obligations (e.g., suspension of the obligation for a certain period, as long as the cause of impossibility of performance lasts, after which the party affected by performance may declare its intention to dissolve the contract).

If the wording of this clause is general (as is often the case), the risk is that it will be of little use; it is also advisable to check that the regulation of force majeure complies with the law applicable to the contract (here an in-depth analysis indicating the regime provided for by 42 national laws).

Applicable law and dispute resolution clauses

Suppose the customer or supplier is based abroad. In that case, several significant differences must be borne in mind: the first is the agreement’s language, which must be intelligible to the foreign party, therefore usually in English or another language familiar to the parties, possibly also in two languages with parallel text.

The second issue concerns the applicable law, which should be expressly indicated in the agreement. This subject matter is vast, and here we can say that the decision on the applicable law must be made on a case-by-case basis, intentionally: in fact, it is not always convenient to recall the application of the law of one’s own country.

In most international sales contracts, the 1980 Vienna Convention on the International Sale of Goods («CISG») applies, a uniform law that is balanced, clear, and easy to understand. Therefore, it is not advisable to exclude it.

Finally, in a supply framework agreement with an international supplier, it is important to identify the method of dispute resolution: no solution fits all. Choosing a country’s jurisdiction is not always the right decision (indeed, it can often prove counterproductive).

Summary

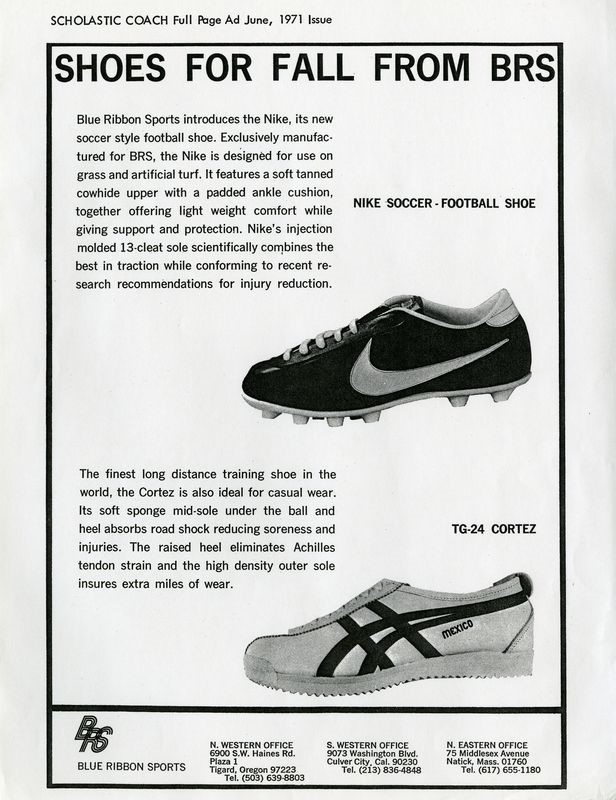

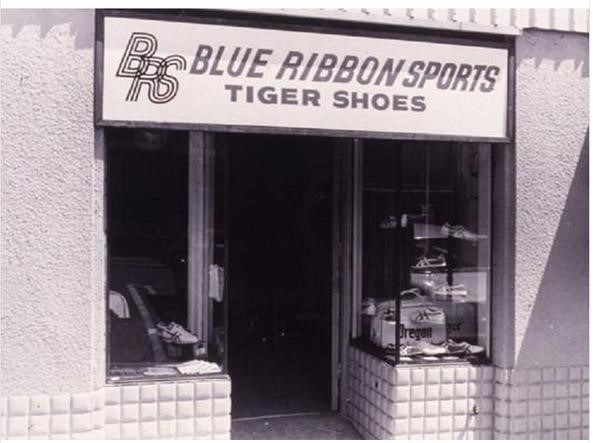

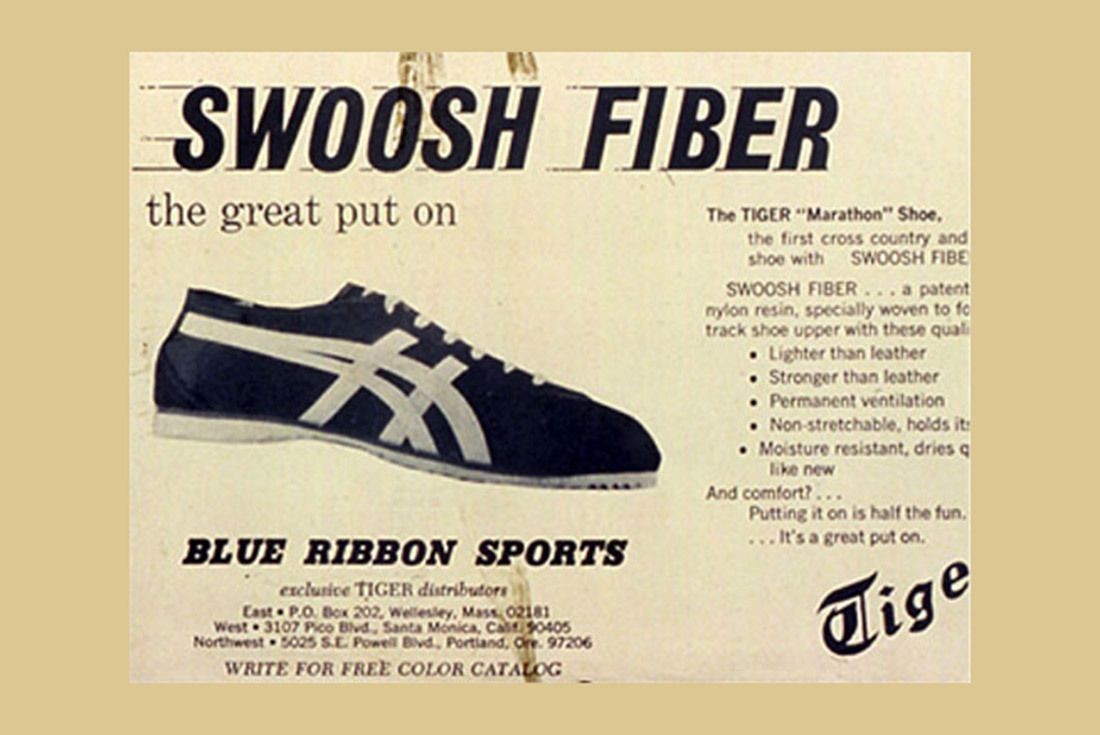

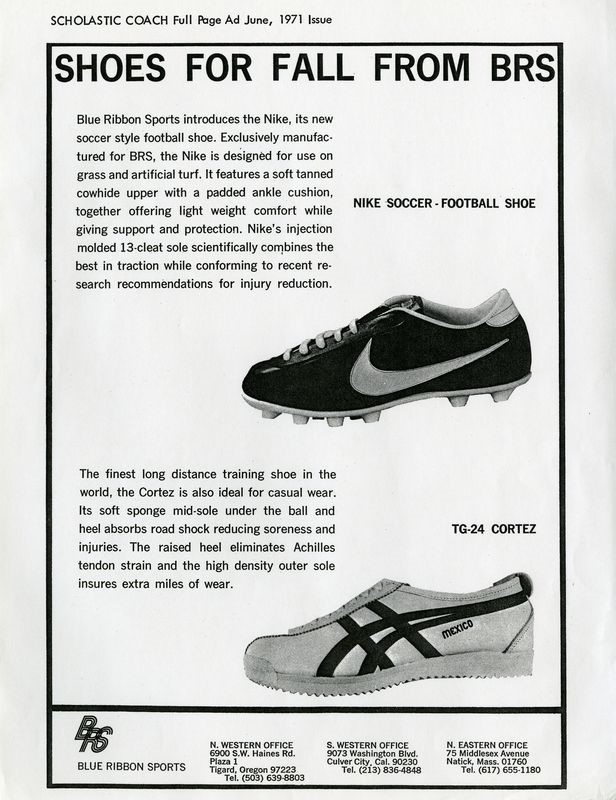

Phil Knight, the founder of Nike, imported the Japanese brand Onitsuka Tiger into the US market in 1964 and quickly gained a 70% share. When Knight learned Onitsuka was looking for another distributor, he created the Nike brand. This led to two lawsuits between the two companies, but Nike eventually won and became the most successful sportswear brand in the world. This article looks at the lessons to be learned from the dispute, such as how to negotiate an international distribution agreement, contractual exclusivity, minimum turnover clauses, duration of the contract, ownership of trademarks, dispute resolution clauses, and more.

What I talk about in this article

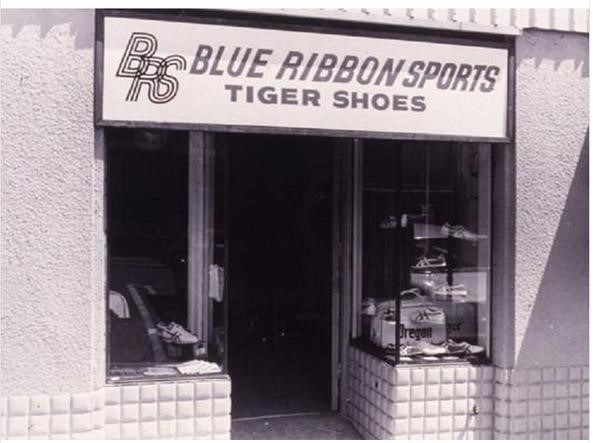

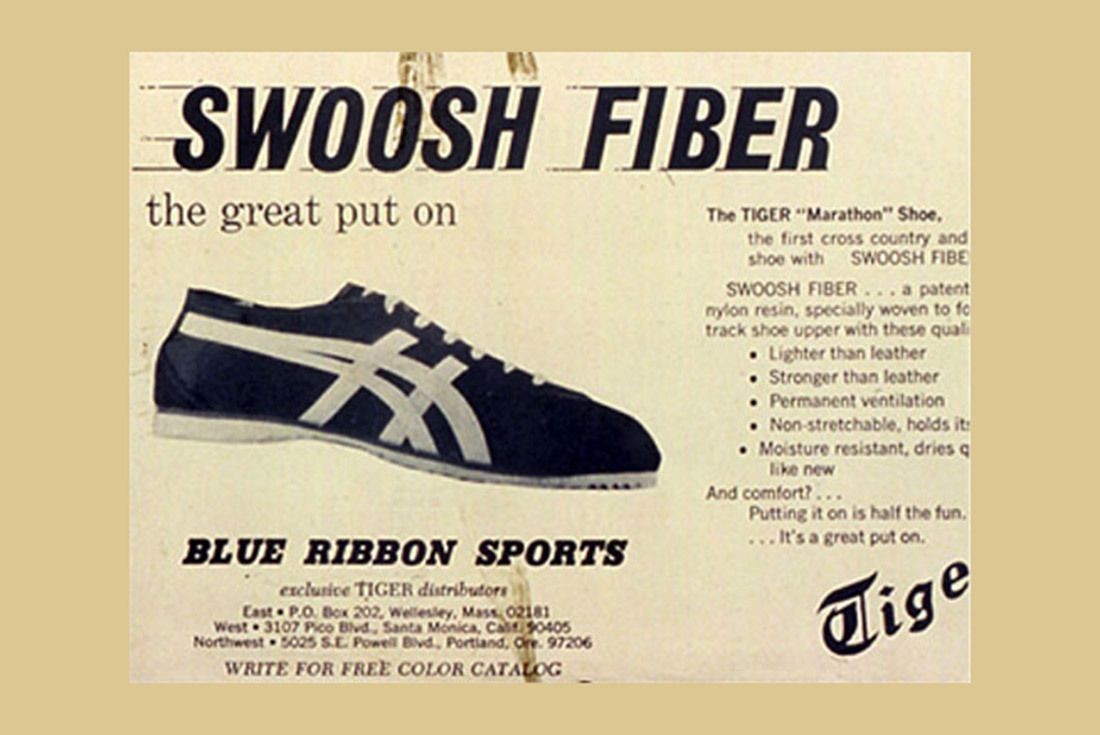

- The Blue Ribbon vs. Onitsuka Tiger dispute and the birth of Nike

- How to negotiate an international distribution agreement

- Contractual exclusivity in a commercial distribution agreement

- Minimum Turnover clauses in distribution contracts

- Duration of the contract and the notice period for termination

- Ownership of trademarks in commercial distribution contracts

- The importance of mediation in international commercial distribution agreements

- Dispute resolution clauses in international contracts

- How we can help you

The Blue Ribbon vs Onitsuka Tiger dispute and the birth of Nike

Why is the most famous sportswear brand in the world Nike and not Onitsuka Tiger?

Shoe Dog is the biography of the creator of Nike, Phil Knight: for lovers of the genre, but not only, the book is really very good and I recommend reading it.

Moved by his passion for running and intuition that there was a space in the American athletic shoe market, at the time dominated by Adidas, Knight was the first, in 1964, to import into the U.S. a brand of Japanese athletic shoes, Onitsuka Tiger, coming to conquer in 6 years a 70% share of the market.

The company founded by Knight and his former college track coach, Bill Bowerman, was called Blue Ribbon Sports.

The business relationship between Blue Ribbon-Nike and the Japanese manufacturer Onitsuka Tiger was, from the beginning, very turbulent, despite the fact that sales of the shoes in the U.S. were going very well and the prospects for growth were positive.

When, shortly after having renewed the contract with the Japanese manufacturer, Knight learned that Onitsuka was looking for another distributor in the U.S., fearing to be cut out of the market, he decided to look for another supplier in Japan and create his own brand, Nike.

Upon learning of the Nike project, the Japanese manufacturer challenged Blue Ribbon for violation of the non-competition agreement, which prohibited the distributor from importing other products manufactured in Japan, declaring the immediate termination of the agreement.

In turn, Blue Ribbon argued that the breach would be Onitsuka Tiger’s, which had started meeting other potential distributors when the contract was still in force and the business was very positive.

This resulted in two lawsuits, one in Japan and one in the U.S., which could have put a premature end to Nike’s history.

Fortunately (for Nike) the American judge ruled in favor of the distributor and the dispute was closed with a settlement: Nike thus began the journey that would lead it 15 years later to become the most important sporting goods brand in the world.

Let’s see what Nike’s history teaches us and what mistakes should be avoided in an international distribution contract.

How to negotiate an international commercial distribution agreement

In his biography, Knight writes that he soon regretted tying the future of his company to a hastily written, few-line commercial agreement at the end of a meeting to negotiate the renewal of the distribution contract.

What did this agreement contain?

The agreement only provided for the renewal of Blue Ribbon’s right to distribute products exclusively in the USA for another three years.

It often happens that international distribution contracts are entrusted to verbal agreements or very simple contracts of short duration: the explanation that is usually given is that in this way it is possible to test the commercial relationship, without binding too much to the counterpart.

This way of doing business, though, is wrong and dangerous: the contract should not be seen as a burden or a constraint, but as a guarantee of the rights of both parties. Not concluding a written contract, or doing so in a very hasty way, means leaving without clear agreements fundamental elements of the future relationship, such as those that led to the dispute between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger: commercial targets, investments, ownership of brands.

If the contract is also international, the need to draw up a complete and balanced agreement is even stronger, given that in the absence of agreements between the parties, or as a supplement to these agreements, a law with which one of the parties is unfamiliar is applied, which is generally the law of the country where the distributor is based.

Even if you are not in the Blue Ribbon situation, where it was an agreement on which the very existence of the company depended, international contracts should be discussed and negotiated with the help of an expert lawyer who knows the law applicable to the agreement and can help the entrepreneur to identify and negotiate the important clauses of the contract.

Territorial exclusivity, commercial objectives and minimum turnover targets

The first reason for conflict between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger was the evaluation of sales trends in the US market.

Onitsuka argued that the turnover was lower than the potential of the U.S. market, while according to Blue Ribbon the sales trend was very positive, since up to that moment it had doubled every year the turnover, conquering an important share of the market sector.

When Blue Ribbon learned that Onituska was evaluating other candidates for the distribution of its products in the USA and fearing to be soon out of the market, Blue Ribbon prepared the Nike brand as Plan B: when this was discovered by the Japanese manufacturer, the situation precipitated and led to a legal dispute between the parties.

The dispute could perhaps have been avoided if the parties had agreed upon commercial targets and the contract had included a fairly standard clause in exclusive distribution agreements, i.e. a minimum sales target on the part of the distributor.

In an exclusive distribution agreement, the manufacturer grants the distributor strong territorial protection against the investments the distributor makes to develop the assigned market.

In order to balance the concession of exclusivity, it is normal for the producer to ask the distributor for the so-called Guaranteed Minimum Turnover or Minimum Target, which must be reached by the distributor every year in order to maintain the privileged status granted to him.

If the Minimum Target is not reached, the contract generally provides that the manufacturer has the right to withdraw from the contract (in the case of an open-ended agreement) or not to renew the agreement (if the contract is for a fixed term) or to revoke or restrict the territorial exclusivity.

In the contract between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger, the agreement did not foresee any targets (and in fact the parties disagreed when evaluating the distributor’s results) and had just been renewed for three years: how can minimum turnover targets be foreseen in a multi-year contract?

In the absence of reliable data, the parties often rely on predetermined percentage increase mechanisms: +10% the second year, + 30% the third, + 50% the fourth, and so on.

The problem with this automatism is that the targets are agreed without having available the real data on the future trend of product sales, competitors’ sales and the market in general, and can therefore be very distant from the distributor’s current sales possibilities.

For example, challenging the distributor for not meeting the second or third year’s target in a recessionary economy would certainly be a questionable decision and a likely source of disagreement.

It would be better to have a clause for consensually setting targets from year to year, stipulating that targets will be agreed between the parties in the light of sales performance in the preceding months, with some advance notice before the end of the current year. In the event of failure to agree on the new target, the contract may provide for the previous year’s target to be applied, or for the parties to have the right to withdraw, subject to a certain period of notice.

It should be remembered, on the other hand, that the target can also be used as an incentive for the distributor: it can be provided, for example, that if a certain turnover is achieved, this will enable the agreement to be renewed, or territorial exclusivity to be extended, or certain commercial compensation to be obtained for the following year.

A final recommendation is to correctly manage the minimum target clause, if present in the contract: it often happens that the manufacturer disputes the failure to reach the target for a certain year, after a long period in which the annual targets had not been reached, or had not been updated, without any consequences.

In such cases, it is possible that the distributor claims that there has been an implicit waiver of this contractual protection and therefore that the withdrawal is not valid: to avoid disputes on this subject, it is advisable to expressly provide in the Minimum Target clause that the failure to challenge the failure to reach the target for a certain period does not mean that the right to activate the clause in the future is waived.

The notice period for terminating an international distribution contract

The other dispute between the parties was the violation of a non-compete agreement: the sale of the Nike brand by Blue Ribbon, when the contract prohibited the sale of other shoes manufactured in Japan.

Onitsuka Tiger claimed that Blue Ribbon had breached the non-compete agreement, while the distributor believed it had no other option, given the manufacturer’s imminent decision to terminate the agreement.

This type of dispute can be avoided by clearly setting a notice period for termination (or non-renewal): this period has the fundamental function of allowing the parties to prepare for the termination of the relationship and to organize their activities after the termination.

In particular, in order to avoid misunderstandings such as the one that arose between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger, it can be foreseen that during this period the parties will be able to make contact with other potential distributors and producers, and that this does not violate the obligations of exclusivity and non-competition.

In the case of Blue Ribbon, in fact, the distributor had gone a step beyond the mere search for another supplier, since it had started to sell Nike products while the contract with Onitsuka was still valid: this behavior represents a serious breach of an exclusivity agreement.

A particular aspect to consider regarding the notice period is the duration: how long does the notice period have to be to be considered fair? In the case of long-standing business relationships, it is important to give the other party sufficient time to reposition themselves in the marketplace, looking for alternative distributors or suppliers, or (as in the case of Blue Ribbon/Nike) to create and launch their own brand.

The other element to be taken into account, when communicating the termination, is that the notice must be such as to allow the distributor to amortize the investments made to meet its obligations during the contract; in the case of Blue Ribbon, the distributor, at the express request of the manufacturer, had opened a series of mono-brand stores both on the West and East Coast of the U.S.A..

A closure of the contract shortly after its renewal and with too short a notice would not have allowed the distributor to reorganize the sales network with a replacement product, forcing the closure of the stores that had sold the Japanese shoes up to that moment.

Generally, it is advisable to provide for a notice period for withdrawal of at least 6 months, but in international distribution contracts, attention should be paid, in addition to the investments made by the parties, to any specific provisions of the law applicable to the contract (here, for example, an in-depth analysis for sudden termination of contracts in France) or to case law on the subject of withdrawal from commercial relations (in some cases, the term considered appropriate for a long-term sales concession contract can reach 24 months).

Finally, it is normal that at the time of closing the contract, the distributor is still in possession of stocks of products: this can be problematic, for example because the distributor usually wishes to liquidate the stock (flash sales or sales through web channels with strong discounts) and this can go against the commercial policies of the manufacturer and new distributors.

In order to avoid this type of situation, a clause that can be included in the distribution contract is that relating to the producer’s right to repurchase existing stock at the end of the contract, already setting the repurchase price (for example, equal to the sale price to the distributor for products of the current season, with a 30% discount for products of the previous season and with a higher discount for products sold more than 24 months previously).

Trademark Ownership in an International Distribution Agreement

During the course of the distribution relationship, Blue Ribbon had created a new type of sole for running shoes and coined the trademarks Cortez and Boston for the top models of the collection, which had been very successful among the public, gaining great popularity: at the end of the contract, both parties claimed ownership of the trademarks.

Situations of this kind frequently occur in international distribution relationships: the distributor registers the manufacturer’s trademark in the country in which it operates, in order to prevent competitors from doing so and to be able to protect the trademark in the case of the sale of counterfeit products; or it happens that the distributor, as in the dispute we are discussing, collaborates in the creation of new trademarks intended for its market.

At the end of the relationship, in the absence of a clear agreement between the parties, a dispute can arise like the one in the Nike case: who is the owner, producer or distributor?

In order to avoid misunderstandings, the first advice is to register the trademark in all the countries in which the products are distributed, and not only: in the case of China, for example, it is advisable to register it anyway, in order to prevent third parties in bad faith from taking the trademark (for further information see this post on Legalmondo).

It is also advisable to include in the distribution contract a clause prohibiting the distributor from registering the trademark (or similar trademarks) in the country in which it operates, with express provision for the manufacturer’s right to ask for its transfer should this occur.

Such a clause would have prevented the dispute between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger from arising.

The facts we are recounting are dated 1976: today, in addition to clarifying the ownership of the trademark and the methods of use by the distributor and its sales network, it is advisable that the contract also regulates the use of the trademark and the distinctive signs of the manufacturer on communication channels, in particular social media.

It is advisable to clearly stipulate that the manufacturer is the owner of the social media profiles, of the content that is created, and of the data generated by the sales, marketing and communication activity in the country in which the distributor operates, who only has the license to use them, in accordance with the owner’s instructions.

In addition, it is a good idea for the agreement to establish how the brand will be used and the communication and sales promotion policies in the market, to avoid initiatives that may have negative or counterproductive effects.

The clause can also be reinforced with the provision of contractual penalties in the event that, at the end of the agreement, the distributor refuses to transfer control of the digital channels and data generated in the course of business.

Mediation in international commercial distribution contracts

Another interesting point offered by the Blue Ribbon vs. Onitsuka Tiger case is linked to the management of conflicts in international distribution relationships: situations such as the one we have seen can be effectively resolved through the use of mediation.

This is an attempt to reconcile the dispute, entrusted to a specialized body or mediator, with the aim of finding an amicable agreement that avoids judicial action.

Mediation can be provided for in the contract as a first step, before the eventual lawsuit or arbitration, or it can be initiated voluntarily within a judicial or arbitration procedure already in progress.

The advantages are many: the main one is the possibility to find a commercial solution that allows the continuation of the relationship, instead of just looking for ways for the termination of the commercial relationship between the parties.

Another interesting aspect of mediation is that of overcoming personal conflicts: in the case of Blue Ribbon vs. Onitsuka, for example, a decisive element in the escalation of problems between the parties was the difficult personal relationship between the CEO of Blue Ribbon and the Export manager of the Japanese manufacturer, aggravated by strong cultural differences.

The process of mediation introduces a third figure, able to dialogue with the parts and to guide them to look for solutions of mutual interest, that can be decisive to overcome the communication problems or the personal hostilities.

For those interested in the topic, we refer to this post on Legalmondo and to the replay of a recent webinar on mediation of international conflicts.

Dispute resolution clauses in international distribution agreements

The dispute between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger led the parties to initiate two parallel lawsuits, one in the US (initiated by the distributor) and one in Japan (rooted by the manufacturer).

This was possible because the contract did not expressly foresee how any future disputes would be resolved, thus generating a very complicated situation, moreover on two judicial fronts in different countries.

The clauses that establish which law applies to a contract and how disputes are to be resolved are known as «midnight clauses«, because they are often the last clauses in the contract, negotiated late at night.

They are, in fact, very important clauses, which must be defined in a conscious way, to avoid solutions that are ineffective or counterproductive.

How we can help you

The construction of an international commercial distribution agreement is an important investment, because it sets the rules of the relationship between the parties for the future and provides them with the tools to manage all the situations that will be created in the future collaboration.

It is essential not only to negotiate and conclude a correct, complete and balanced agreement, but also to know how to manage it over the years, especially when situations of conflict arise.

Legalmondo offers the possibility to work with lawyers experienced in international commercial distribution in more than 60 countries: write us your needs.

Finalmente, tras más de 30 años de negociaciones, el mundo está ante el primer acuerdo comercial panafricano, que entró en vigor a principios de 2019: la Zona de Libre Comercio Continental Africana (African Continental Free Trade Area – AfCFTA).

África, con sus 55 países y unos 1.300 millones de habitantes, es el segundo continente más grande del mundo después de Asia. El potencial del continente es enorme: más del 50 % de la población africana tiene menos de 20 años y está creciendo al ritmo más rápido del mundo. Para 2050, se espera que uno de cada cuatro recién nacidos sea africano. Además, el continente es rico en suelo fértil y materias primas.

Para los inversores occidentales, África ha cobrado una importancia considerable en los últimos años. El auge del comercio internacional en este continente, entre otras cosas, es promovido por la iniciativa “Pacto con África” adoptada por los países del G20 en 2017, también conocida como el “Plan Marshall con África”. Su objetivo es ampliar la cooperación económica de África con los países del G20 reforzando la inversión privada.

Sin embargo, el comercio intraafricano actualmente ha estado estancado por causa de los aranceles intraafricanos, en parte todavía elevados, las barreras no arancelarias (non-tariff barriers – NTBs), la debilidad de las infraestructuras, la corrupción, la engorrosa burocracia, así como las normativas poco transparentes e incoherentes. Esto ha provocado que las exportaciones interregionales apenas pudieran desarrollarse y, más recientemente, solo representan el 17 % del comercio panafricano y sólo el 0,36 % del comercio mundial. Hace ya mucho tiempo que la Unión Africana (UA) incluyó en su agenda la creación de una zona comercial común.

¿Qué hay detrás del AfCFTA?

La creación de una zona de comercio panafricana estuvo precedida de décadas de negociaciones, que finalmente desembocaron en la entrada en vigor del AfCFTA el 30 de mayo de 2019.

El AfCFTA es una zona de libre comercio establecida por sus miembros, que -con la excepción de Eritrea- abarca todo el continente africano y es, por tanto, la mayor zona de libre comercio del mundo por número de Estados miembros después de la Organización Mundial del Comercio (OMC).

La estructuración detallada del mercado común fue objeto de varias negociaciones individuales, que se debatieron en las Fases I y II.

La Fase I comprende las negociaciones sobre tres protocolos y está casi concluida.

El Protocolo sobre el comercio de mercancías

Este protocolo prevé la eliminación del 90 % de todos los aranceles intraafricanos en todas las categorías de productos en un plazo de cinco años a partir de su entrada en vigor. De estos, hasta un 7 % de los productos pueden clasificarse como mercancías sensibles, que están sujetas a un periodo de eliminación arancelaria de diez años. Para los países menos adelantados (Least Developed Countries – LDCs), el periodo de preparación se amplía de cinco a diez años y para los productos sensibles de diez a trece años, siempre y cuando demuestren su necesidad. El 3 % restante de los aranceles queda totalmente exento del desarme arancelario.

Adicionalmente, debe tenerse en cuenta que el requisito previo para el desarme arancelario es la delimitación clara de las normas de origen. De lo contrario, las importaciones de terceros países podrían beneficiarse de las ventajas arancelarias negociadas. Ya se ha alcanzado un acuerdo sobre la mayoría de las normas de origen.

El Protocolo sobre el Comercio de Servicios

La Asamblea General de l’UA ha acordado hasta ahora cinco áreas prioritarias (transporte, comunicaciones, turismo, servicios financieros y empresariales) y directrices para los compromisos aplicables a las mismas. Hasta la fecha, 47 Estados miembros de l’UA han presentado sus ofertas de compromisos específicos y se ha completado la revisión de 28 de ellos. Además, siguen en curso las negociaciones, por ejemplo, sobre el reconocimiento de las cualificaciones profesionales.

El Protocolo sobre Solución de Diferencias

Con el Protocolo sobre normas y procedimientos por los que se rige la solución de diferencias, el AfCFTA crea un sistema de solución de diferencias inspirado en el Entendimiento sobre Solución de Diferencias de l’OMC. En virtud del mismo, el Órgano de Solución de Diferencias (Dispute Settlement Body – OSD) administra el Protocolo de Solución de Diferencias del AfCFTA y establece un Grupo Especial Adjudicador (Adjudicating Panel – Panel) y un Órgano de Apelación (Appellate Body – AB). El DSB está compuesto por un representante de cada Estado miembro e interviene en cuanto existen diferencias de opinión entre los Estados contratantes sobre la interpretación y/o aplicación del acuerdo en lo que respecta a sus derechos y obligaciones.

Para el resto de la Fase II están previstas negociaciones sobre política de inversión y competencia, cuestiones de propiedad intelectual, comercio en línea y mujeres y jóvenes en el comercio, cuyos resultados se reflejarán en posteriores protocolos.

La aplicación del AfCFTA

En principio, la aplicación del comercio en virtud de un acuerdo comercial sólo puede comenzar una vez que se haya aclarado definitivamente el marco jurídico. Sin embargo, los Jefes de Estado y de Gobierno de l’UA acordaron en diciembre de 2020 que el comercio puede comenzar para los bienes cuyas negociaciones hayan finalizado. En virtud de este “acuerdo transitorio”, tras un aplazamiento relacionado con la pandemia, el primer acuerdo comercial AfCFTA de Ghana a Sudáfrica tuvo lugar el 4 de enero de 2021.

Elementos constitutivos del AfCFTA

Los 55 miembros de l’UA participaron en las negociaciones de la AfCFTA. De ellos, 47 pertenecen al menos a una – y algunos a más de una – Comunidades Económicas Regionales (Regional Economic Communities – RECs) reconocidas, que, según el preámbulo del acuerdo AfCFTA, deben seguir siendo los bloques de construcción del acuerdo comercial. Por tanto, fueron ellas las que actuaron como portavoces de sus respectivos miembros en las negociaciones del AfCFTA. El AfCFTA prevé que las RECs conserven sus instrumentos jurídicos, instituciones y mecanismos de resolución de conflictos.

Dentro de l’UA, hay ocho REC reconocidas, que se solapan en algunos países, y que son acuerdos comerciales preferenciales (Free Trade Agreements – FTAs) o uniones aduaneras.

En el marco del AfCFTA, las RECs tienen diversas responsabilidades. Se trata, en particular, de:

- coordinar las posiciones negociadoras y asistir a los Estados miembros en la aplicación del acuerdo;

- mediación orientada a la búsqueda de soluciones en caso de desacuerdo entre los Estados miembros;

- apoyar a los Estados miembros en la armonización de aranceles y otras normativas de protección fronteriza;

- promover el uso del procedimiento de notificación del AfCFTA para reducir las barreras no arancelarias.

Perspectivas de la AfCFTA

El AfCFTA tiene el potencial de facilitar la integración de África en la economía mundial y crea la posibilidad real de un reajuste de los modelos de integración y cooperación internacionales.

Un acuerdo comercial por sí solo no es garantía de éxito económico. Para que el acuerdo logre el avance previsto, los Estados miembros deben tener la voluntad política de aplicar las nuevas normas de forma coherente y crear la capacidad necesaria para ello. En particular, la eliminación a corto plazo de las barreras comerciales y la creación de una infraestructura física y digital sostenible serán probablemente cruciales.

Si está interesado en el AfCFTA, puede leer una versión ampliada de este artículo aquí.

Legalmondo Africa Desk

Ayudamos a las empresas a invertir y hacer negocios en África con nuestros expertos en Argelia, Túnez, Marruecos, Egipto, Ghana, Sudán, Libia, Senegal, Côte d’Ivoire, Camerún y Malawi.

También podemos ayudar a entidades extranjeras en países africanos en los que no estamos presentes directamente con una oficina a través de nuestra red de socios locales.

Cómo funciona

- Concertamos una reunión (en persona o en línea) con uno de nuestros expertos para entender las necesidades del cliente.

- Una vez que empezamos a trabajar juntos, atendemos al cliente con un abogado que se encarga de todas sus necesidades legales (casos individuales, o asistencia jurídica continua).

Póngase en contacto para saber más.

Contacta con Christophe

Distribution Contracts in Spain

30 agosto 2023

-

España

- Contratos de distribución

El agente comercial tiene derecho a obtener cierta información sobre las ventas del empresario. La Ley española del Contrato de Agencia prevé (15.2 LCA) que el agente tiene derecho a exigir la exhibición de la contabilidad del empresario para verificar todo lo relativo a las comisiones que le correspondan. Y también a que se le proporcionen las informaciones de que disponga el empresario y que sean necesarias para verificar la cuantía de dichas comisiones.

Este artículo está en consonancia con lo previsto en la Directiva sobre los agentes comerciales de 1986 según la cual (12.3) el agente tendrá derecho a exigir que se le proporcionen todas las informaciones que se hallen a disposición del empresario, en particular un extracto de los libros de contabilidad, que le sean necesarias para verificar el importe de las comisiones que le correspondan. Esto no podrá alterarse en detrimento del agente comercial mediante pacto.

La pregunta es ¿permanece este derecho incluso tras la terminación del contrato de agencia? En otras palabras: extinguido el contrato de agencia, ¿puede el agente solicitar la información y documentación mencionada en estos artículos y está el empresario obligado a proporcionársela?

En nuestra opinión, la norma no dice nada que limite este derecho, más bien cabe pensar lo contrario. Por lo que, en la medida en que persista alguna posible comisión que pueda nacer de dicha verificación, la respuesta ha de ser afirmativa. Veamos.

El derecho a exigir la exhibición de la contabilidad existe para que el agente pueda verificar la cuantía de las comisiones. Y el agente tiene derecho a comisiones por actos y operaciones concluidos durante la vigencia del contrato (art. 12 LCA), pero también por actos u operaciones concluidos con posterioridad a la extinción del contrato (art. 13 LCA), y por operaciones no ejecutadas por circunstancias imputables al empresario (art. 17 LCA). Además, el agente tiene derecho a que la comisión se devengue en el momento en que hubiera debido ejecutarse el acto u operación (art. 14 LCA).

Todas estas operaciones pueden tener lugar una vez concluido el contrato. Piénsese en la situación habitual en la que los pedidos se cursan durante el contrato, pero son aceptados o ejecutados con posterioridad. Reducir el derecho del agente a informarse solo durante la vigencia del contrato sería limitar indebidamente su derecho a la comisión correspondiente. Y téngase en cuenta que el importe de las comisiones durante los últimos cinco años puede, además, influir en el cálculo de la indemnización por clientela (art. 28 LCA), por lo que el interés del agente para conocerlas es doble: lo que percibiría como comisión, y lo que podría aumentar la base para una futura indemnización.

Esto ha sido confirmado, por ejemplo, por la Audiencia de Madrid (AAP 227/2017, de 29 de junio [ECLI:ES:APM:2017:2873A]) que textualmente dice:

[…] el art. 15.2 de la ley de Contrato de Agencia dispone el derecho del agente a exigir la exhibición de la contabilidad del empresario en los particulares necesarios para verificar todo lo relativo a las comisiones que le corresponden, como a serle proporcionadas las informaciones de que disponga el empresario y sean necesarias para verificar su cuantía. A ello no es óbice, […], que el contrato de agencia ya hubiese sido resuelto pues ello no implica que dejasen de devengarse comisiones por pólizas, contratadas con la mediación del agente, que mantengan su vigencia.

Cabe preguntarse entonces si este derecho de información es ilimitado en el tiempo. Y aquí la respuesta sería negativa. La limitación del derecho a recibir información estaría vinculada a la prescripción del derecho a reclamar la correspondiente comisión. Si el derecho a percibir la comisión estuviera indudablemente prescrito, podría defenderse que no cabría recibir información sobre ella. Pero para tal excepción, la prescripción debe ser clara, por lo tanto, considerando las posibles interrupciones habidas por reclamaciones incluso extrajudiciales. En caso de duda, será necesario reconocer el derecho a exigir la información, sin perjuicio de que luego se invoque y reconozca la imposibilidad de reclamar la comisión si estuviera prescrito el derecho. Y para ello debemos considerar el plazo de prescripción para exigir las comisiones (en general, tres años) y la del derecho para reclamar la indemnización por clientela (un año).

En resumen: no parece que el derecho a recibir información y al examen de la documentación del empresario quede limitado por la vigencia del contrato de agencia; aunque, por otra parte, convenga analizar la posible prescripción para exigir las comisiones. En caso de no tener una respuesta clara sobre ésta, el derecho de información debería, en nuestra opinión, prevalecer, sin perjuicio de que el resultado pueda luego no dar derecho a la reclamación por haber prescrito.

SUMMARY: In large-scale events such as the Paris Olympics certain companies will attempt to «wildly» associate their brand with the event through a practice called «ambush marketing», defined by caselaw as «an advertising strategy implemented by a company in order to associate its commercial image with that of an event, and thus to benefit from the media impact of said event, without paying the related rights and without first obtaining the event organizer’s authorization» (Paris Court of Appeal, June 8, 2018, Case No 17/12912). A risky and punishable practice, that might sometimes yet be an option yet.

Key takeaways

- Ambush marketing might be a punished practice but is not prohibited as such;

- As a counterpart of their investment, sponsors and official partners benefit from an extensive legal protection against all forms of ambush marketing in the event concerned, through various general texts (counterfeiting, parasitism, intellectual property) or more specific ones (e.g. sport law);

- The Olympics Games are subject to specific regulations that further strengthen this protection, particularly in terms of intellectual property.

- But these rights are not absolute, and they are still thin opportunities for astute ambush marketing.

The protection offered to sponsors and official partners of sporting and cultural events from ambush marketing